The Failure of Reconstruction—And Its Consequences

July 27, 2022

This summer, Ashbrook offered a graduate course on Civil War and Reconstruction for teachers as part of its Master of Arts in American History and Government program (MAHG). It was an experience the teachers involved would never forget.

Senior Fellow David Tucker, who edited the Ashbrook document collection Slavery and Its Consequences, led the opening session, devoted to reflecting on the Civil War in American memory. He asked teachers enrolled in the course what ideas about the war their students brought to history class. They reported students’ confusion about the war’s cause.

Reconciliation Overrides Principle

Their students reflect a national amnesia that took root within a generation of the exhausting fratricidal conflict. Reconciliation became more important than clarity about why the southern states seceded. When historians of the defeated Confederacy reframed the rebellion as a principled assertion of states’ rights, their arguments were treated respectfully. Generations of textbook-reliant history teachers followed suit.

Not so the teachers beginning the MAHG course. Already well-read in primary sources on the antebellum period, they soon agreed that “without a doubt, slavery was the cause of the war,” as a teacher named Scott, of North Dakota, said. Among the general public, however, “You often see a complete disconnect from the truth,” said Jody of Tennessee.

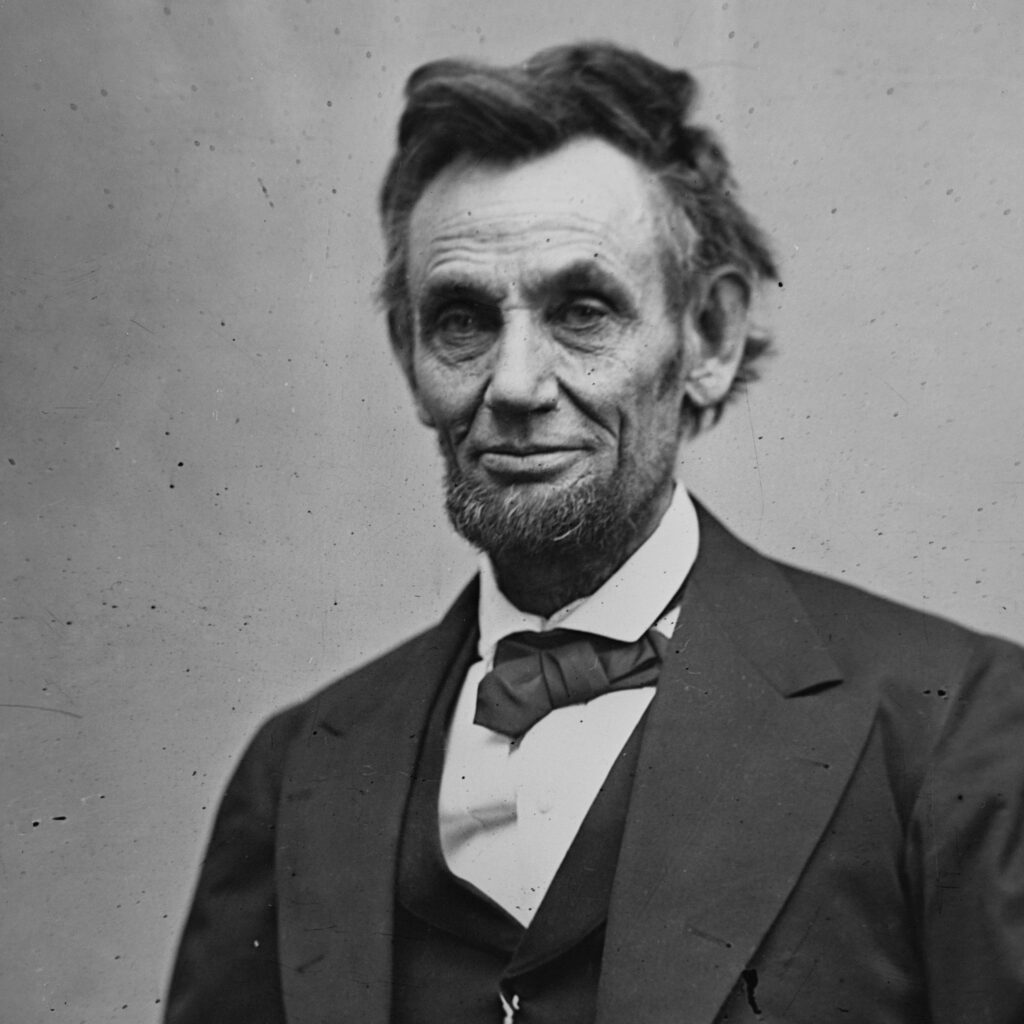

The issue is complicated by President Lincoln’s carefully calibrated war aims. Teachers knew that the Southern states seceded in the expectation that Lincoln’s election would lead to the end of slavery. Yet teachers also knew that Lincoln’s initial war aim was restoring the union, not ending slavery. They knew that Lincoln turned toward emancipation only after concluding that freeing the enslaved would weaken the secessionist cause, ending the war and restoring the union.

The Failure to Study Reconstruction

After declaring emancipation, Lincoln pushed the Thirteenth Amendment through Congress, permanently ending slavery throughout the nation. What teachers most wanted to learn was why the Thirteenth, along with the Fourteenth and Fifteenth, Amendments—all passed during Reconstruction—failed to ensure the citizenship rights of the freed people. “That’s why I’m taking this course,” Jody announced. “I’m trying to figure out what went wrong during Reconstruction.” Why did a century of racial oppression ensue?

Teachers agreed that if African Americans remain disadvantaged in America’s social, economic, and political life, it is because of Reconstruction’s failure. They admitted difficulties in teaching Reconstruction, not only because textbooks often minimize the subject, but because it typically falls at the end of the “US History, part I” course taught in the eighth grade in many states. “My eighth graders never come back mentally from spring break,” said Massachusetts teacher Ethan. High school students rarely revisit the subject, unless they are taking advanced placement US history, a fast-paced survey of events in America from European discovery and settlement to the present.

The Current Controversy

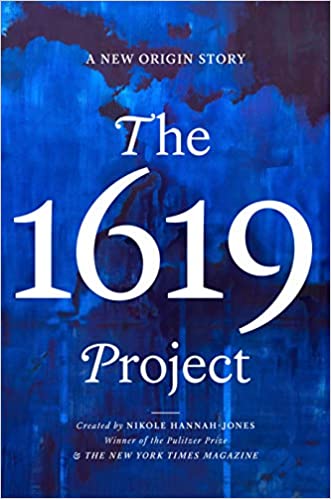

The assigned reading for the first session of the MAHG course included Nicole Hannah-Jones’ lead essay for the “1619 project” (along with a critique of the essay authored by MAHG professor Lucas Morel). Jones won a Pulitzer Prize for the essay, which highlighted aspects of the shameful history of slavery most Americans haven’t been taught. However, prominent historians objected to Jones’ central contention: that from the outset, Americans intended to found a republic based on slave labor. Historians challenged Jones’ claim that the founders designed the Constitution to uphold slavery, despite the Declaration’s announcement of human equality and liberty. They also objected to Jones’ claim that Abraham Lincoln did not see black and white Americans as equals, either.

Teachers found Jones’ argument replete with factual errors and strained interpretations. Jones failed to mention the many arguments over slavery during the Constitutional Convention, they said. She also ignored the will left behind by George Washington, added Seth, a teacher from Ohio. It freed the enslaved people held by Washington and provided for their education.

Lincoln’s Commitment to Liberty

Thomas, a teacher from New Hampshire, cited Lincoln’s private note to himself, the Fragment on the Constitution and Union, which likens the Constitution to a frame of silver around a painting of golden apples: it was designed to protect and uphold the principle of “Liberty to all”, as Lincoln put it. Like other teachers, Thomas argued Lincoln wanted to abolish slavery, but worried that assimilating the newly emancipated into America’s civic life would be difficult.

Many Americans harbored prejudices against African Americans, similar to the prejudices they harbored against each new immigrant group, Jody added. While insisting on their equality with others in their own ethnic group, they made little room for those outside. “Even if you could have made southerners” respect the civil rights of African Americans, Jody asked, “what would you do about northerners and westerners?”

In her “1619 Project” essay, Jones describes a meeting Lincoln held with black leaders in 1862, in which he asked them to endorse the resettlement of emancipated slaves in an African or Caribbean colony. Jones says this showed Lincoln’s unwillingness to invite African Americans into full citizenship. Paul, from Washington, objected that Lincoln did not really expect to win the black leaders’ agreement to a colonization plan. “He already knew their answer would be ‘No!’ Yet I think he did foresee the long struggle Africans Americans would face as they asked to be treated equally.”

Lincoln “could not simply say to the freedmen, ‘Come to the north,’” said Ethan. Given the hostility of many white laborers toward competition in the labor market, a mass migration of freedmen to the north would have been a political and social nightmare. Lincoln probably “had a better pulse on the actual attitudes of Americans toward black people than the abolitionists and radical Republicans did,” Paul agreed. Traveling through Illinois as a trial lawyer, Lincoln saw plentiful evidence of racial prejudice. In presenting the colonization option, Kyle from Idaho said, “he was just checking off the boxes,” speaking beyond the black leaders to the nation at large, exhausting every scheme for emancipation the public would easily accept. He had already asked the border states to accept compensated emancipation. Rebuffed on both counts, he proceeded with emancipation anyway.

1619 and the Truth of History

“I see this essay (by Nicole Hannah-Jones) as one of the most dangerous things I could ever give my students to read,” Jody finally exclaimed. “It presents history without its context. It cherry-picks those facts” that seem to condemn Lincoln and the founders as hypocrites. “I could see my students saying, ‘Oh my gosh! This essay shows what a terrible nation we really are!’”

Still, given the publicity the 1619 Project has received, students can easily find summaries of its claims online. Perhaps, Jody and her colleagues concluded, they should ask students to read the essay—and help them read it critically.

Teaching students to carefully assess the history of American slavery requires time and patience—at a time when state-mandated tests, AP curricula, and the march of time itself push many teachers to forgo depth for breadth. It requires careful review of the primary documents. The teachers in MAHG take the time for this, because, as Professor Tucker asserted, they are responsible for teaching young citizens the honest truth of American history.

Part of this truth appears in James Madison’s notes on the debates in the Constitutional Convention, which record repeated condemnations of slavery as immoral. Madison’s account also records threats from delegates from the Carolinas and Georgia that they would refuse to sign any document that limited slavery. It quotes other delegates urging compromise, so as to prevent the young nation from splitting apart. It shows Madison objecting to any use of the word “slave” or “slavery,” lest such mention be taken as an endorsement of a practice he and others hoped would eventually disappear.

Debates at the convention and later show Northern states, which had few slaves, moving to forbid slavery within their own borders. They show many Northerners acknowledging their principles, but hanging onto prejudices. But they show an abandonment of principle in the places where slavery became strongly entrenched. This was especially so after the cotton gin made cotton a highly profitable export crop. Slavery spread, becoming more important in the American economy. If people in slave states could not give up slavery, they also could not defend slavery while professing the Declaration’s ideals. It’s no surprise, then, that at the outbreak of civil war, Vice President of the Confederacy Alexander Stephens formally renounced the Declaration’s claim that all men are created equal in his “Cornerstone Speech,” proclaiming instead that the new Confederate government was “founded upon exactly the opposite idea . . . , upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

The Long Fight for Civil Rights

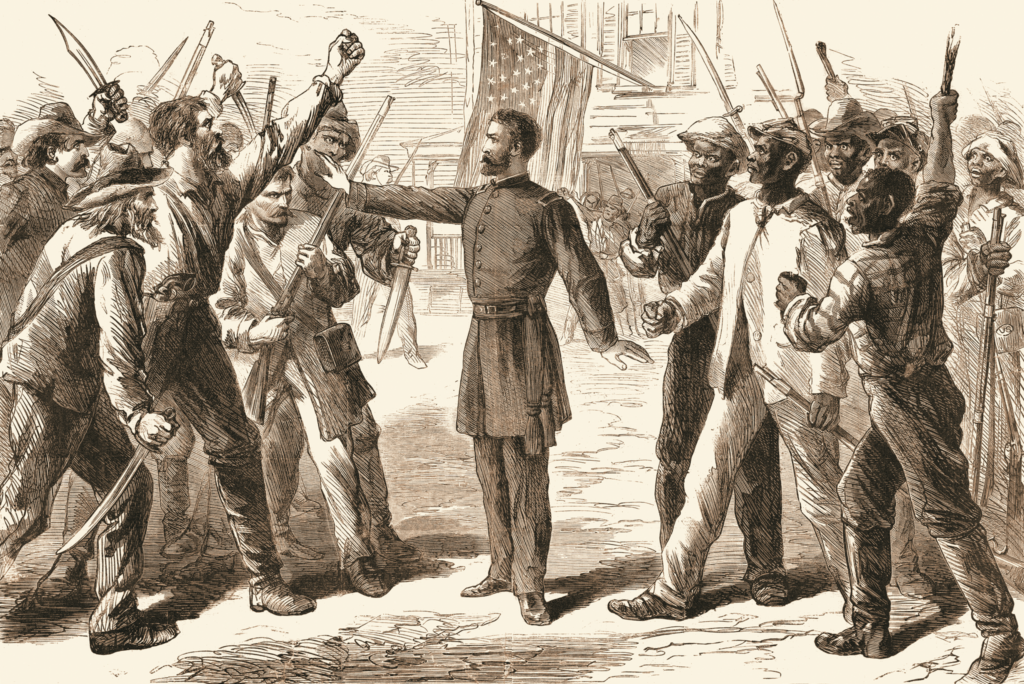

By the end of the first session of the course, teachers were eager to read the story of Reconstruction in the primary documents. Yet they already glimpsed the reasons Reconstruction failed. To succeed, Reconstruction would have required people who were reliant on slavery to give up not only prejudice but also their sense of entitlement to cheap black labor. It would also have required they admit a political principle they’d rejected.

Teachers agreed with Jones that the story of American slavery and its many consequences should be told in greater depth. They took Jones’ point that African Americans themselves led the civil rights cause. Fighting for equal rights throughout the century following emancipation, black Americans developed a strategy of nonviolent resistance that has been imitated by other seeking freedom and full citizenship. Students need to learn this. But they should also learn a point Jones denies: civil rights activists haven’t fought alone. Other Americans have fought alongside them. And throughout the struggle, they had the Declaration of Independence, which has stood throughout the years, inspiring and guiding their efforts to realize the promise of America’s Founding principles.