Teaching Lessons from Lincoln’s Lyceum Address

December 24, 2020

Miles Matthews, who teaches at the John Adams Academy in Roseville, CA (a public charter school north of Sacramento; it offers a “classical” education to students of all ability levels; admission is by lottery) made a connection with Jeremy Gypton, Ashbrook Teacher Program Manager, about three years ago, through one-day and multi-day events. Matthews enjoys the seminars very much, particularly one in April 2019 on the USS Midway, focused on the Cold War. Matthews has been using many of our document collections in his 11th grade US history classes. Here’s his testimony:

“This past year I downloaded a pdf version of the World War II documents and put together a packet of them to use in class; they fit very well with our curriculum. This year I’m using all but four chapters of both volumes of Documents and Debates. TAH has given me tons of good stuff to work with. . . . I’m using your collections now more than ever. They work really well with the distanced learning we’re now doing, because you can still hold really good Socratic discussions once you get past the barrier of the Zoom platform itself. Instead of doing traditional work page assignments, which I don’t do a ton of anyway, we’re doing more reading, writing and discussion.

“I was just writing questions for a discussion we’re having tomorrow in our Zoom class meeting. Students have been reading Federalist 1, 10 and 51; the US Constitution; and Docs and Debates, chapter 7, which includes Jefferson’s letter to Madison in which he says “If we cannot secure all our rights, let us secure what we can”. It’s fun to figure out how to have a conversation about that—even to have a conversation with the authors of the documents. They definitely speak to me. I hope they also speak to the kids.

“As I go through Federalist 10, I’m thinking about the current protests that become violent. We’ve been seeing mob rule, in a lot of ways. Madison discusses the passions of faction. If Americans could only read this, they’d see this is not something new; it is the very stuff that the founders worried about. . . .

“It’s not so hard for students to see a connection to today. Sometimes I point to the current example, but often I just leave it to them to make the connection. Then I don’t have to be that teacher who’s dragging politics into the classroom. I’ve been a student in classes like that, and I think it shuts down debate. Students feel they had better not challenge the teacher.

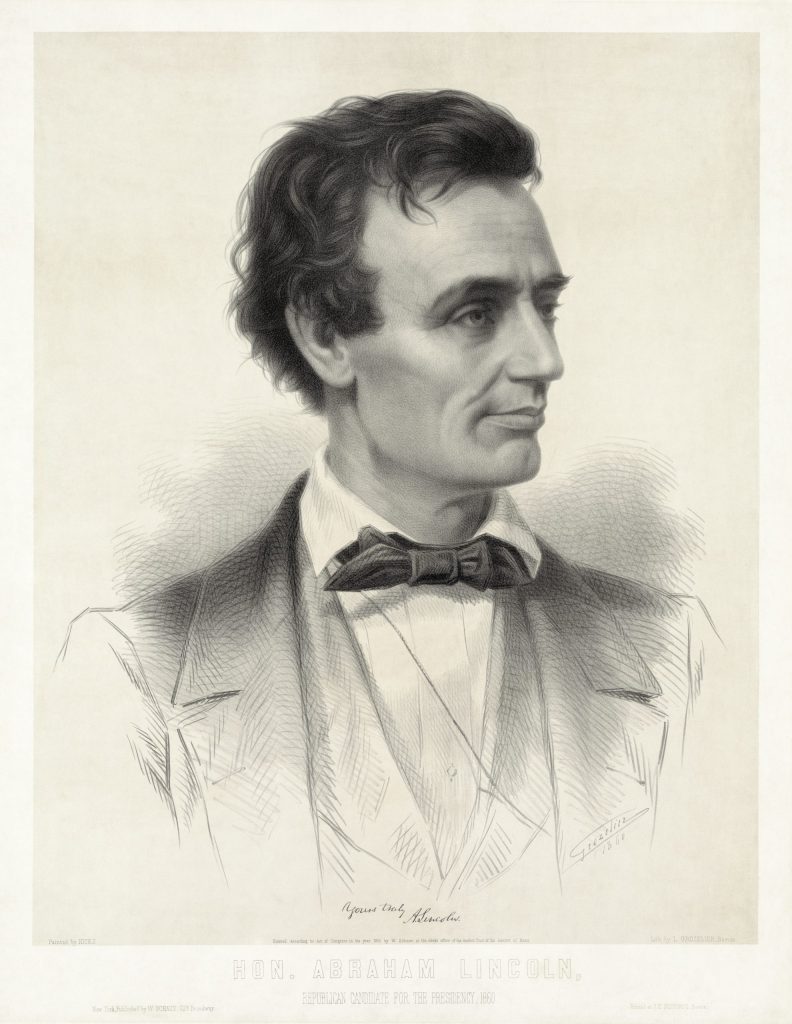

“This summer I was reading Lincoln’s Lyceum Speech and thought, ‘he’s talking about exactly what we’re seeing—a breakdown of society due to mob rule!’ I decided to present this document on day one of the school year. I told students to read it and think about it. Then I asked them, ‘Why does mob rule threaten free government? Why was Lincoln so worried about it?’ A couple of kids said, ‘Hey, this is like what’s happening in Portland.’ I let them talk about that for a few minutes, then drew them back to 1838, so we could continue analyzing Lincoln’s argument. If teachers get too political, they are telling kids what to think instead of letting them decide for themselves—instead of acting as a mentor or guide in how to think. My students have told me they appreciate that I don’t make things too political; some have even said, ‘I have no idea what your politics are!’ It should be that way. We don’t have to tell kids that mob rule is horrible. They can see it. They need to come to grips with it on their own. I feel that the TAH documents are excellent for that.”

“This summer I was reading Lincoln’s Lyceum Speech and thought, ‘he’s talking about exactly what we’re seeing—a breakdown of society due to mob rule!’ I decided to present this document on day one of the school year. I told students to read it and think about it. Then I asked them, ‘Why does mob rule threaten free government? Why was Lincoln so worried about it?’ A couple of kids said, ‘Hey, this is like what’s happening in Portland.’ I let them talk about that for a few minutes, then drew them back to 1838, so we could continue analyzing Lincoln’s argument. If teachers get too political, they are telling kids what to think instead of letting them decide for themselves—instead of acting as a mentor or guide in how to think. My students have told me they appreciate that I don’t make things too political; some have even said, ‘I have no idea what your politics are!’ It should be that way. We don’t have to tell kids that mob rule is horrible. They can see it. They need to come to grips with it on their own. I feel that the TAH documents are excellent for that.”