Honest History and Hope in Ojibwe Classroom

May 1, 2023

“In my Native American history class, I’m trying to step back a little from all the negative history,” says Reid Benson, who is in his 12th year of teaching history at Cass Lake-Bena High School, located on the Leech Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota. Most of the school’s students are members of the Ojibwe nation. “I’m trying to focus on the questions, ‘How can we be positive going forward? How are we going to make our communities better and be proactive in protecting our rights?’” Still, an honest account of the past necessarily undergirds these hopeful questions, Benson says. A 2018 graduate of Ashbrook’s graduate program, Benson continues to study, extending his ability to give students that honest account. In fact, he continues taking courses with Ashbrook.

It’s a sign of Benson’s commitment that he doesn’t just audit these additional courses; he takes them for continuing education credit, submitting the required exams and essays. Earlier in life, Benson considered studying in a research-oriented master’s program in history, before realizing he was not interested in the minutiae of research. Doing the coursework for Ashbrook, he’s “not worried about citations and footnotes—stuff that doesn’t seem all that important to me.” The program “is more about reading and thinking and talking about what you’re reading” with other dedicated teachers.

Ashbrook’s graduate program doesn’t require teachers to write a thesis based on original research on an arcane topic. (Those students who choose the thesis or capstone option as their culminating work typically write on topics of broader interest, topics they expect to cover in their teaching. Other students opt to take a cumulative exam.) Nor does Ashbrook offer courses in pedagogy, like the Masters in History Education offered at many universities. Ashbrook’s graduate program “assumes that you’re a pretty decent teacher already.” It aims “to teach you how to be . . . a better historian. That appeals to me quite a bit.”

What Inhibits Honesty About the Past

“You can never teach everything there is to know” about America, Benson admits. Teachers must cover various learning standards within strict time limits. Because he uses primary documents, Benson must also devote a lot of class time to helping students learn to read carefully and critically. Still, he continues to educate himself. “A strong content knowledge allows you to pick and choose the history you cover in more astute ways.” It “makes you more confident in your delivery. Students are smart; they get it when you know your stuff,” Benson says. “Knowing your stuff” earns students’ respect and trust.

Benson says he cannot inspire students to consider “the possibilities” of American life without first “acknowledging all the terrible, terrible atrocities” against Native American and other minority communities. The Americans who did these things acted in disregard of their own admirable principles. “What my students find frustrating is the fact that so many Americans don’t acknowledge these things.”

This lack of acknowledgement owes, he thinks, to ignorance. “It’s surprising how little historical knowledge many Americans have. For example, people are often stunned to learn that one third of Native Americans weren’t citizens prior to the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.” American Indian history is slighted in most US history courses—in part, Benson notes, because the documentary record is “patchy.” Some tribal languages were never alphabetized. The tribes preserved their history in the stories they told from one generation to the next. Few learned English in order to record their own perspectives on events. Many Native American primary sources are translated versions of speeches overheard by whites claiming knowledge of their authors’ languages. We cannot always be sure of their accuracy.

Benson’s students don’t usually enter his classroom knowing a lot about their own history, either. Besides their sense of having been displaced from their original tribal lands, the students are most aware of the boarding school educations forced on many of their elders. “The majority of my students know that a grandparent, or somebody else in their family, was a victim of boarding schools,” Benson says. According to a report recently released by the Department of the Interior, between 1819 and 1969 over 400 Indian boarding schools received federal funding. Most were established to prepare indigenous youth to assimilate into white culture. Some children were coerced into enrolling. Most of the schools forbade children from speaking their own tribal languages, even with friends outside of class. Designed to disrupt transmission of Native American culture, the boarding school program effectively disrupted transmission of Native American history, also.

Historical Memory and Academic Achievement

Because of this legacy, Benson and his colleagues struggle against the community’s distrust of academic achievement. The small school—with 222 students in grades nine through twelve—sends “between a half dozen to a dozen” of its yearly graduates to post-secondary schools. Some study in vocational programs such as nursing; some gifted athletes are recruited to college basketball teams. “I haven’t seen any of my students go into history yet. But we have some successful engineers and we’re beginning to see a few going into teaching. Seeing more indigenous graduates returning as teachers would be great for our community.”

Teaching indigenous youth, Benson takes care to highlight their ancestors’ impact on our country. Knowing this story will help them ‘to carve out their own space” in American society. Yet all Americans should study Native American history, Benson feels, just as Native Americans should study the broad sweep of American history. Everyone should examine the complicated processes by which our ancestors interpreted and applied—or failed to apply—their own political principles.

The Power of Primary Documents

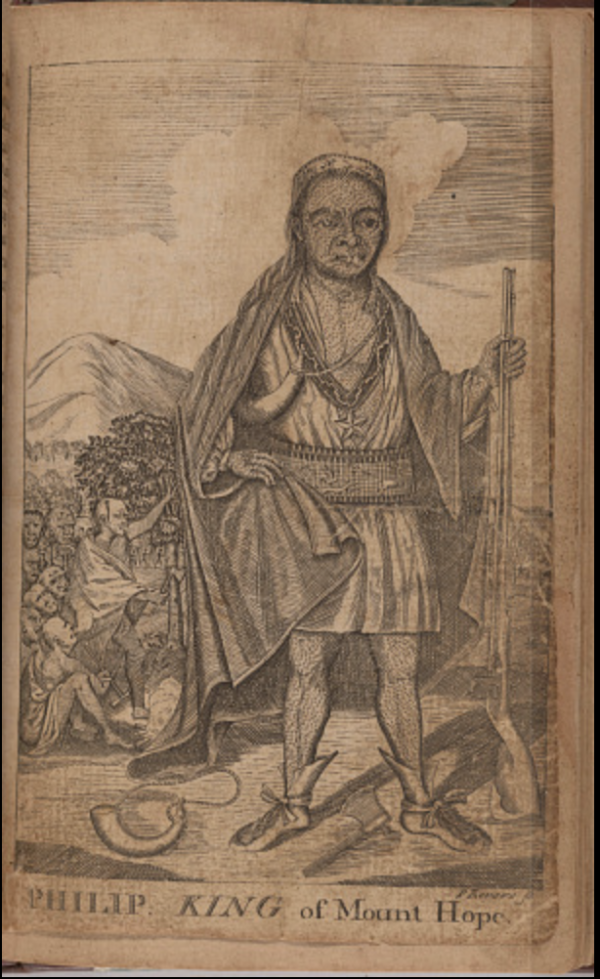

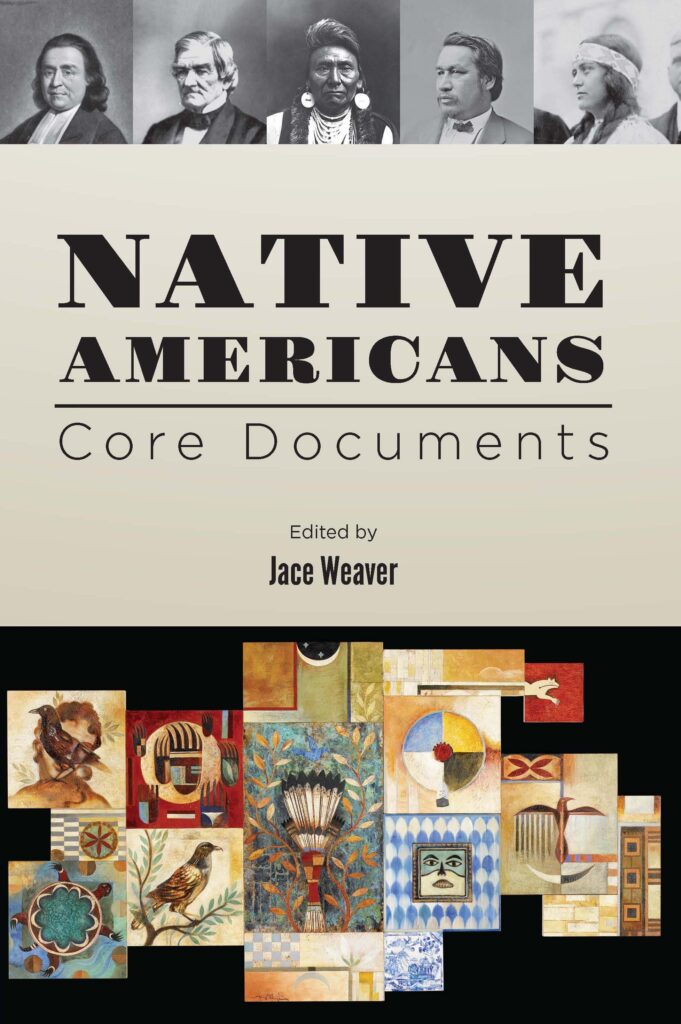

Primary documents give students an honest account of the past, at least from the perspective of those who lived in the past and recorded their experiences. Eager to discover new Indian-authored texts, Benson recently read through Teaching American History’s core document collection, Native Americans, edited by Jace Weaver. He has already added nine of its documents to his curriculum. These selections span the 17th through 20th centuries. Reid has used the earliest, which records John Eastman’s 1675 interview with Metacomet (known to English settlers as King Philip), in which he explains the causes of the war of resistance he led against settlers in New England. He’s also used some 20th century documents, including the proclamation issued by 89 Native American activists who occupied an abandoned federal prison facility on Alcatraz Island in 1969.

Benson teaches almost entirely through primary documents, having realized during his Ashbrook studies that the sources that fascinated him could also engage students. “Talking to some of the other teachers in the program, I realized I didn’t need to do anything that didn’t involve primary sources. I do selectively use secondary sources, but I don’t use a textbook. I think I’m a better teacher because of it.”

Primary sources reveal the thinking of past generations. “Reading a couple paragraphs of Alexander Stephens’s Cornerstone speech is a really effective way to show that white supremacy was alive and well in the Confederacy. Reading all of the Gettysburg Address doesn’t take a lot of time, but you can pull some really, really important themes out of it.” Lincoln tells his war-weary auditors that their fight tests “the proposition that all men are created equal,” and Benson’s students see that Lincoln is quoting from “the second paragraph of the Declaration,” a statement of American political principles they earlier discussed in detail. Students realize that some Americans, like the Confederates, have rejected the founders’ avowed belief in human equality. Others have not “lived up to” it. Some, like Lincoln, work to recenter American life around the principle.

The Human Agency in Events

An honest account of the past acknowledges the human agency in events. The social and political “systems” citizens participate in, systems that lend cover and sanction to injustices, cannot be discounted in history study, Benson thinks. However, “systems are harder for kids to understand” than the telling narrative about a citizen or leader’s consequential decision. “We recently observed the 160th anniversary of the 38 Dakota men who were executed in Mankato, the largest mass execution in American history. Lincoln was president at the time, so a lot of people want to throw him under the bus. Actually, he reduced the number of those sentenced to death from 392 to 38. It’s amazing that he took the time out of the Civil War to even pay any attention to the sentencing of these men. Part of our job as history teachers is to give more of that nuance.”

Today, more and more of America’s difficult history is aired in the news. Giving high school students an honest account of the past–one with detail and nuance–inoculates them against disillusionment and helps them think constructively about the future. During the year following the murder of George Floyd, as our history of racial injustice was publicly probed, university students around America protested on social media platforms: “Why were we never taught this?” A university student who’d taken Benson’s honors class posted a different comment: “I can’t relate to what you all are saying. Mr. Benson taught us all these things in high school.”

Exceptional Principles, Fallible Human Beings

The history of injustices against Native Americans involves “people being people, for the most part,” Benson says—for example, greedy middlemen who took government funds meant to provision Indians journeying to reservations; settlers who seized Indian lands in violation of treaties; annuity payments that went missing. These stories contradict many Americans’ understanding of our nation as exceptional. Giving an honest account of the past “doesn’t mean we can’t hold up American political principles as exceptional,” Benson says. But we have to think about how to make them function, practically speaking.

“I also try to find stories that emphasize the positive,” he says. He can’t be sure that many of his students will continue their study of history. “You have to decide which stories to hammer home and which to just mention and then move on.” He talks about heroic Native American military service, celebrates the appointment of Deb Haaland as Secretary of the Interior, and carefully selects books as gifts to graduating seniors. He emphasizes the rights and responsibilities of citizens. “The 14th amendment declares all of us equal under the law,” he tells students. “I encourage activism, working to create the America you want to see—not letting other people do it for you. We’ve got to start with our own actions in our own communities.”

Watch a film of teachers at Benson’s school reciting their “protocols”–that is, stating their names, clans, and home communities—in the Ojibwe language. Students in an honors class at the high school coached the teachers as they learned their protocols. You can see Benson at 1 min., 25 seconds.