Ashbrook Professor Named Female Faculty Member of the Year

December 24, 2020

Professor Emily Hess of Ashland University’s History and Political Science Department was named Outstanding Female Faculty Member of the Year at the Ashland University Leadership and Service Awards ceremony on April 13. She was nominated for this honor by Student Senate and Tau Kappa Epsilon Fraternity, in letters noting her enthusiasm, ability to make American history interesting even to non-majors, willingness to provide guidance to students outside of the classroom, and innovative teaching methods. Students remarked on her use of a teaching method called “Reacting to the Past.” We talked with Dr. Hess about her teaching work at Ashland University.

Would you explain how “Reacting to the Past” works?

Professor John Moser introduced me to this approach, which asks students to role-play characters interacting in an historical moment. For example, after studying the sectional crisis that led to the Civil War, we turned the classroom into the Kentucky legislature in 1860. Students played legislators debating, after Lincoln’s election as President, whether to secede or stay in the Union. One student was a banker worried about financial security; another a hemp planter who saw Lincoln as a raging abolitionist; another the reluctant heir to a slave fortune. The object of the game was not to replicate what the Kentucky legislature decided in 1860, but to help students understand the issues legislators dealt with.

A professor who assigns this must let go of the reins. Students direct the classroom, showing how much they are capable of. To prepare for this exercise, they will not only do the required reading, they’ll find extra sources to read. They want to win the game!

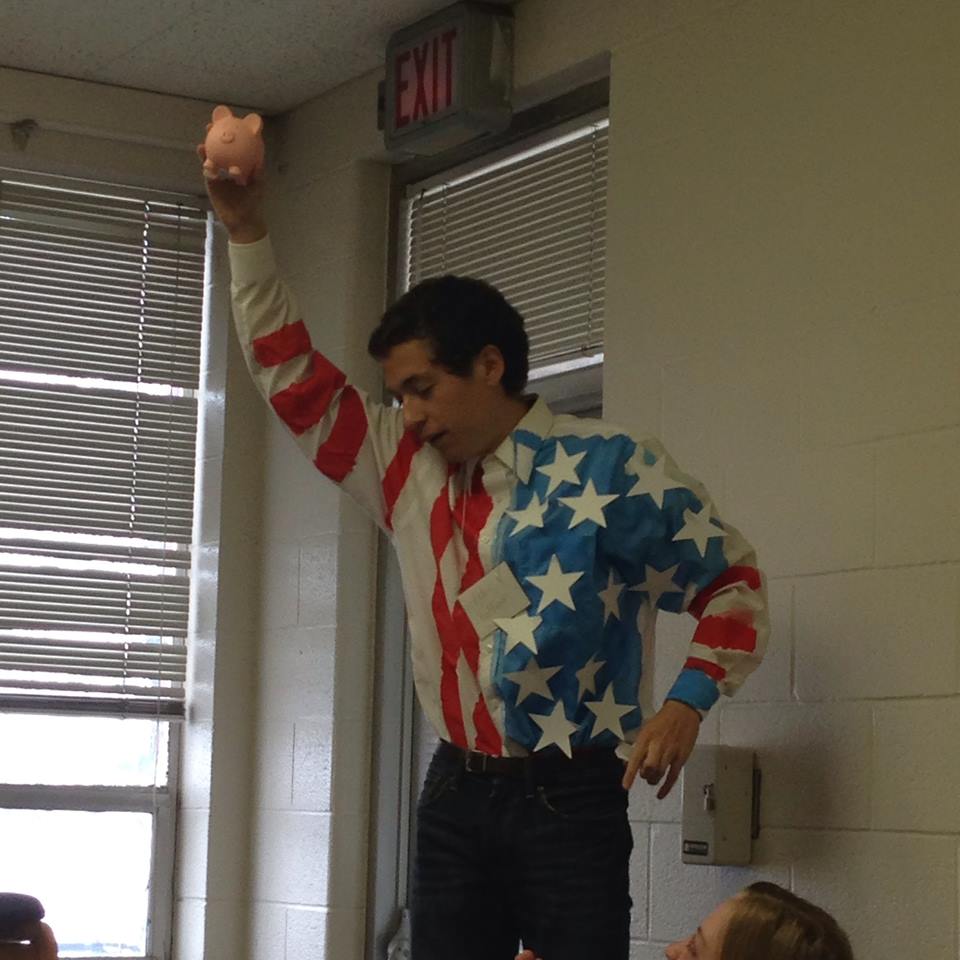

In my honors course on post-Civil War history, we reenacted the 1968 Democratic Convention. Students really got into their roles. One dressed up in an American flag shirt and carried a toy pig to impersonate Abbie Hoffman railing against the presidential candidates and saying that a pig would make a worthier nominee. Another who played a candidate showed he had researched his opponents when he pointed to Lester Maddox, announcing that he had not graduated from high school. Taken aback, the student playing Maddox said, “I didn’t know that about my character!” The student playing Hubert Humphrey saw me outside of class and said, “I’ve been so stressed out trying to keep the Democratic Party together!” The exercise teaches some life skills students need, since they don’t usually take courses on building coalitions, speaking extemporaneously, or debating.

Clearly you enjoy interacting with students. What else do you enjoy about your work at AU?

I enjoy working with colleagues in the History and Political Science department who share a vision of what it means to teach in a student-centered program. All want their students to leave class still thinking about what was discussed and making connections to other courses, always reflecting on human nature and the individual’s place in society.

The department emphasizes the value of depth over breadth. Peter Schramm advised me, “You can be comprehensive, or you can be true.” History can so easily become a timeline of dates and facts to memorize. In this department, students discover that history is complicated. Those who shaped events did not act in unison, marching in line with the mood of the moment.

What are your goals as a teacher?

I hope students realize that the questions historical figures wrestled with are still important. For example, I might ask them to consider what 19th century abolitionist Frederick Douglass would say today about affirmative action or multiculturalism. When a student says to me, “I started reading that book because you assigned it, but when I got into it I found it really fascinating,” I ask them why. Inevitably they bring up some theme of the book that gives them hope and supports perseverance toward their goals.