A Lively Conversation on America

December 24, 2020

It’s late morning on the eighth-floor of the library, and the elevator door slides open to the Ashbrook Center, spilling out an impossibly numerous and boisterous group of students. These are freshmen Ashbrook Scholars who’ve trooped over together from Mishler House for their spring seminar, “Democracy in America.” Close quarters don’t bother them; nor does the uninterrupted and often edgy discussion of their shared living and study space. They seat themselves in groups of five or six, ready to kick off class with a little friendly competition—a quick quiz of useful facts, extra credit points to the winning team—before settling down to a close, guided reading of an essential American document.

It’s late morning on the eighth-floor of the library, and the elevator door slides open to the Ashbrook Center, spilling out an impossibly numerous and boisterous group of students. These are freshmen Ashbrook Scholars who’ve trooped over together from Mishler House for their spring seminar, “Democracy in America.” Close quarters don’t bother them; nor does the uninterrupted and often edgy discussion of their shared living and study space. They seat themselves in groups of five or six, ready to kick off class with a little friendly competition—a quick quiz of useful facts, extra credit points to the winning team—before settling down to a close, guided reading of an essential American document.

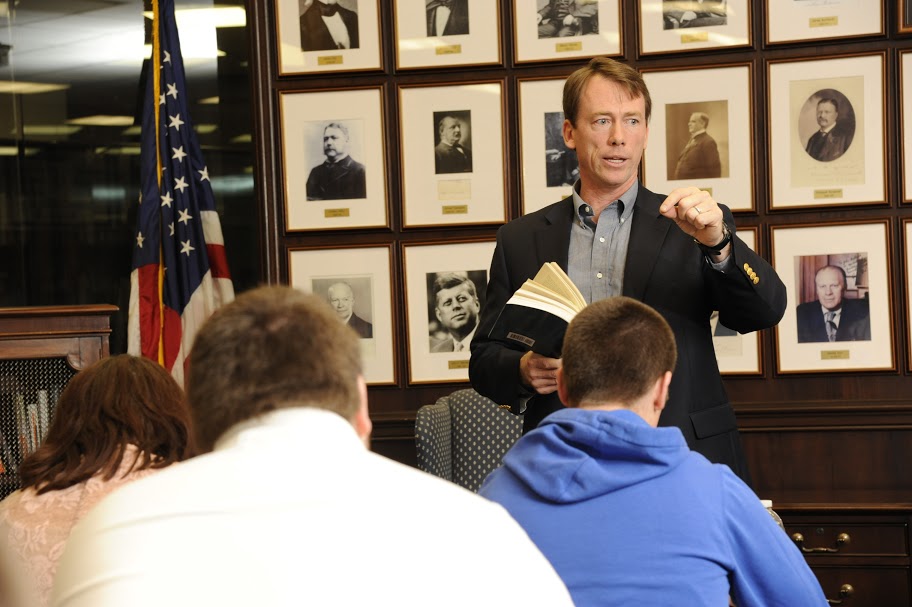

Professor Jeffrey Sikkenga seizes the attention of almost thirty pairs of eyes, directing them to a line in the Declaration of Independence. They are taking the document apart clause by clause, questioning the meaning of key phrases. The Declaration begins, “When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bonds connecting them with another . . . .” Sikkenga stops the reading to ask in what sense the Americans of 1776, spread across thirteen colonies with distinct climates, customs, economies and ethnic compositions, were a single people. Before this point in human history, what factors caused national groups to see themselves as united? Students propose answers, eventually agreeing that a shared race, religion, or subjugation to a single ruler had defined national groups. How, then, could the thirteen colonies see themselves as one people? Students begin to see that Americans were united by shared political principles.

The Declaration will spell those principles out, but students will need to read closely, stopping to investigate the meaning of key ideas, such as “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” This will carry them into discussion of a tradition of political philosophy that informed the Declaration as well as forward into the structure of the US Constitution, which shaped the principles of the Declaration into political institutions and practices.

“The course is an immersion in the fundamental political ideas and institutions of America,” Sikkenga explains. It prepares Scholars for their second year of history and political science study, when they take two semesters of American Political Thought, reviewing in detail the written arguments, criticisms, and applications of American principles. “But it also gives students the foundation they need as citizens.”

Sikkenga challenges students to articulate what they’ve learned in essay assignments that apply American principles, such as the idea of human equality, to problems in American history, such as the glaring fact of slavery. Were the Founders immoral to overlook the practice of slavery as they established their republic? Or did they act as statesmen?

A specialist in Constitutional law, Sikkenga will also ask students to apply the Founders’ understanding of property rights to later Supreme Court decisions. In their final exam he may ask them to play the role of Constitutional advisor to a President attempting a nationalization of industry in wartime. Through assignments like these, students don’t just “regurgitate their notes; they take what they’ve learned and think through how it applies in a practical situation, making a reasoned argument.”

Managing discussion in a class of about thirty highly engaged students is “always a challenge,” Sikkenga concedes. “They like thinking out loud, discussing, and disputing. By this point they’ve come to know each other well, and the conversation can take on the tone of a family argument. I remind them at times, ‘Don’t make it personal.’ But they usually govern themselves. After their fall semester course with Dr. Schramm, they’ve gotten good at this kind of conversation.”

Sikkenga is a highly accomplished scholar who, among other work, has co-written The Free Person and the Free Economy (2002), co-edited the collection History of American Political Thought (Lexington Press, 2003), and is now writing a study of John Locke’s “Letter Concerning Toleration,” which influenced the thinking of Jefferson and Madison on religious freedom. Nevertheless, he envies the undergraduate experience Ashbrook Scholars are enjoying.

“They are vastly better educated than I was as an undergraduate. They know primary sources in a way that I did not. They have read the work of thinkers and statesmen whom I’d just kind of heard of.”Ashbrook Scholars also benefit from the coherent design of their whole course of study, Sikkenga said. “They thoroughly enjoy their lively engagement with ideas while they are here, but when they go back out into the world, they realize just how special their education really was.”