Civic Education, Rightly Understood

March 30, 2022

In a time of deep division and despair in America, where can we find hope for the future of our country? Dr. Wilfred M. McClay explores this question, making the case that civic education, grounded in a truthful telling of American history, can be one source for answers.

Dr. McClay’s most recent book is the award-winning Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story, a text which aims to provide readers with an honest and inspiring account of American history.

We live in anxious times. But there have been many times in our past that were far more anxious, and in which the reasons for anxiety were far more compelling. We must remember that.

Consider, for example, the situation facing the world in the early months of 1941, when Hitler’s triumphant armies controlled continental Europe, when only the British Isles managed to hold out, and when the future of liberty looked very dim—indeed, when civilization itself seemed imperiled. Yet at that moment, the novelist John Dos Passos chose to pen these words:

In times of change and danger when there is a quicksand of fear under men’s reasoning, a sense of continuity with generations gone before can stretch like a lifeline across the scary present….

It must have been tempting for him to declare, as journalists like to do, that the present situation was utterly without precedent, and the past had nothing to teach the present. After all, had the world ever before seen a more fearsome and pitiless fighting machine than the one Adolph Hitler had assembled? But Dos Passos chose to convey an exactly opposite message. He urged that we look backward, reaching back to a past that could be a source of sanity and direction, a lifeline of sustenance and instruction.

An Education for Democratic Citizenship

Such training of the mind ought to be at the very core of an education for democratic citizenship. We neglect an essential element in the formation of our citizens when we fail to supply our young people with a full, accurate, and responsible account of their own country. That is what the formal study of American history should provide. Our knowledge of such things does not come to us automatically, by birth or cultural osmosis. The knowledge must be acquired, and, once taken in, needs to be made our own, a part of our shared consciousness and our common memory.

And that is something we are consistently failing to do. The evidence of our failure is overwhelming and incontestable. In fact, the most recent test administered by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, sometimes called “The Nation’s Report Card,” shows continuing decline in already low history and geography scores and flatlining in civics scores. The explanations adduced for this abysmal performance are many, and the barriers thrown up by the surrounding culture are formidable. But the bottom line is that we must recommit ourselves to the teaching of both history and civics—and the recognition that the two belong together. As Eliot Cohen of Johns Hopkins University has aptly expressed it, “Without history, there is no civic education, and without civic education there are no citizens. Without citizens, there is no free republic. The stakes, in other words, could not be higher.”

A Connection to the Past

All of which is true—and the stakes are indeed that high. But there is something more that needs attending to in the work of civic education. Tracking scores on standardized tests can provide useful, if limited, data about the state of our historical knowledge. But they cannot tell us about the depth and quality of that knowledge or the extent to which those who possess it feel a genuine and living connection to it—that is, a felt connection to their own past. That connection is what we most need to recover and restore. It is as much a task of the heart as it is of the head.

“Citizenship” is a word that has lost much of the noble luster it once had, just as “civics” has been demoted to little more than a kind of “user’s guide” to the machinery of government. Both words deserve far better. Citizenship is not merely about voting. It is about membership in a society of civic equals: citizens, not subjects, whose respect for one another’s equal standing under the law is a guiding moral premise of the democratic way of life.

Civic education is not only about how a bill becomes a law. It is about promoting a vivid and enduring sense of our belonging to one of the greatest enterprises in human history: the astonishing, perilous, and immensely consequential story of our own country. Both things involve fostering that sense of felt connection to our past, and of gratitude for the good things that we have inherited, along with a feeling of responsibility for the tasks of preserving them and improving upon them. Hence a civic education should be an initiation not only into a canon of ideas, but into a community; and not just a community of the present, but a community of memory—a long human chain linking past, present, and future in shared recognition and, one hopes, in gratitude.

An Education In Love

Ultimately, in fact, a patriotic education should be an education in love. Make no mistake: The love we are talking about is something different from romantic or familial love, something that cannot be imposed by teachers or schools or government edicts, least of all in a free country. Like any love worthy of the name, it must be embraced freely and be strong and unsentimental enough to coexist with the elements of disappointment, criticism, dissent, opposition, and even shame that come with moral maturity and open eyes. But it is love all the same, and without the deep foundation it supplies, a republic will perish.

I have been speaking in abstractions, though, so let me give a concrete example of what I am talking about. It is a particularly powerful example since it involves a great leader who possessed an enormously powerful sense of connection to the past, even though he was largely self-educated: Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln’s Civic Education

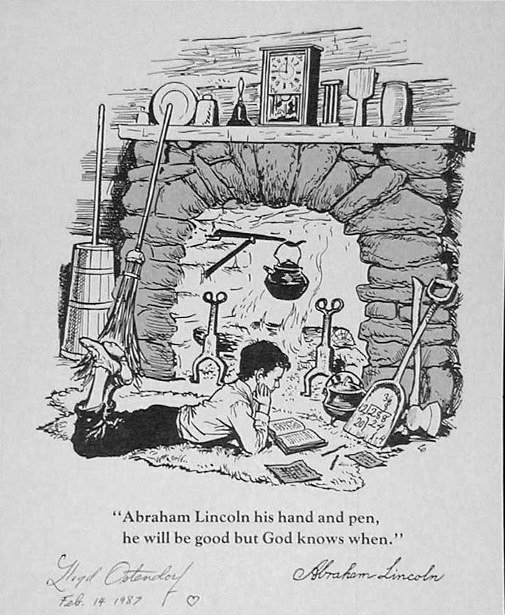

Young Abraham Lincoln reading by the fireplace in their Indiana cabin.

by Lloyd Ostendorf. (Source: https://americangallery.wordpress.com

/2012/11/02/lloyd-ostendorf-1921-2000/)

We all know that Lincoln was a voracious reader. He had essentially no formal education and acquired his peerless sense of the English language from reading, including Shakespeare’s plays and the King James Bible. But it appears that he read almost no history in his younger days. The sole exception that we know of was Mason Weems’s 1799 biography of George Washington, a tome few would read today, and certainly not for its accuracy. After all, it is the book from which the fable of young George chopping down the cherry tree came.

The mature Lincoln went on to develop a far more informed and sophisticated understanding of history. And yet essential traces of Weems’s History stayed with him all his life, an enduring deposit in his mind and heart that would influence his view of the American Revolution and the Civil War and reflect his fundamental values.

How do we know this? We know it because in February of 1861, 40 years after he first read Weems’s book, Lincoln drew upon it explicitly. He was on his way from Illinois to Washington to be inaugurated as President. It was a time of extraordinary tension in the land, as Southern states were voting to drop away from the Union one after another in response to Lincoln’s election. There was real reason to believe that the nation was in the process of disintegrating.

Lincoln stopped off in Trenton, New Jersey, on his way to Washington, and gave a short but powerful speech to the New Jersey State Senate, in which he recalled the effect of Weems’s book on him as a young man. He particularly remembered Weems’s account of the Battle of Trenton, one of the pivotal moments in the American Revolution, stating, “I remember all the accounts there given of the battle fields and struggles for the liberties of the country, and none fixed themselves upon my imagination so deeply as the struggle here at Trenton, New-Jersey”

The crossing of the river; the contest with the Hessians; the great hardships endured at that time, all fixed themselves on my memory more than any single revolutionary event; and you all know, for you have all been boys, how these early impressions last longer than any others. I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for.

That “something more than common” was, he continued, “something even more than National Independence; that something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world to all time to come.”

Lincoln was “exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made,” and he hoped that he could be “an humble instrument in the hands of the Almighty, and of this, his almost chosen people, for perpetuating the object of that great struggle.”

What a lot for a youthful story to do! It shaped a boy’s mind and soul in ways that would have such enormous consequences for the man—and for all of us. That story, those “early impressions,” helped him to form a compelling vision of the American past—a vision both inspiring and true that would sustain him through the dark days to come.

Note too that, although himself a fierce opponent of slavery, Lincoln did not focus on George Washington’s history as a slaveowner, even though he knew of it. He did not entertain the view, fashionable among Southern planters then and New York journalists now, that the nation was founded on slavery. No, he insisted, it was founded on other principles entirely, principles of liberty and equality and self-rule that were something new in the world, principles that America was born to champion. He was right then, and he is right now.

So what are we to conclude from this example? Do historians need to retool and start writing inspiring fables like those of Mason Weems instead of hardheaded and dispassionate factual accounts of the past, based on careful and methodical research? Absolutely not. History must be based on truth, not on myth. We do ourselves and our young no favors by prettifying or oversimplifying the past and failing to give an honest account of our failures as well as our triumphs.

A Vessel of Shared Memory

But we also do no favors to ourselves or to the truth if we fail to honor the magnificent achievements of our history and leave them out of our accounting entirely, as has become too often the case. We need to remember that one of the civic functions of history, one of the chief reasons we endeavor to record the past and teach it to our young, is to serve as a vessel of shared memory, imparting to each generation a sense of membership in its own society, a sense of living connection to its own past—a sense that can unite us and sustain us in hard times.

Lincoln brought that very connection to many of his best speeches, most notably to his speech at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg on November 19, 1863.

Just as he had done in Trenton, so he did in Gettysburg, even as war raged around him, reaching back to the nation’s birth in 1776—“ four score and seven years ago”—as one of the great achievements in human history, a precious legacy to whose preservation the deeds of the present ought to be dedicated. He found in the American past a source of sustenance, a steadying influence in a time buffeted by chaos and fear, a source of renewed courage and determination.

So can it be for us. Our young people deserve nothing less. We are failing them, and our country, so long as we fail to give them a rich and sustaining sense of their own past, a sense that is both truthful and inspiring. It is high time that we did.

The Inglorious Story

Consider the alternative. If a great story of estimable things can give us courage and hope in a hard time, does it not stand to reason that the promulgation of an inglorious story of relentless failure, mendacity, and despoilation can have the opposite effect? For the Inglorious Story, too, is a kind of civic education.

We are tenderly solicitous of the “safety” of college students who may be exposed to ideas or words that they may find upsetting. But why do we not think about the effects of the Inglorious Story that they are taking in? Doesn’t their picture of the world they inhabit profoundly affect their sense of their life’s possibilities and prospects? Shouldn’t we consider whether the remarkably high indicators of unhappiness among our young people—and not only young people—are partly traceable to a massive loss of morale and hope? Suicides among Americans aged 10 to 24 increased by nearly 60 percent between 2007 and 2018.

A Pew study found rising rates of depression, especially among teenage girls, and that 70 percent of teens think anxiety and depression are major problems for their peers. Roughly 50 percent see alcohol and drug addiction as major problems.

The list of pathologies goes on and on.

I am deeply concerned about these statistics, as any sensible person should be. It is hard not to think that they presage a kind of general moral collapse. No one would deny that there are material factors, such as the dizzying and disorienting changes in the structures of the national and world economy at work in these trends. But the morale of a nation is ultimately a question of spirit rather than matter. One cannot deny that, by moving into the vacuum left by the absence of a genuine civic education, as well as the decline of traditional religion and the decay of traditional structures of family life, the Inglorious Story has been gaining the upper hand on us, playing a powerful role in sustaining our low morale, saturating our young in debilitating ideas about the past, present, and future—leaving them isolated and anxious.

In an otherwise noncommittal recent story in USA Today about the suicide epidemic, there is this stunning statement: “Many children, experts say, are struggling to imagine their futures.” Indeed they are. But this should not be a mystery to us.

Conclusion

The great Austrian psychiatrist Victor Frankl, himself a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps, observed that we humans can bear almost any kind of material deprivation and suffering—except for the deprivation of meaning.

Those of us who have a reason to live, who have a task or a goal toward which our strivings can be directed, who have a “why” that animates our lives, can bear up under almost any hardship. But without that “why” almost any “how” can defeat us, and overturn our best intentions and hopes.

Such matters go far deeper than civics. But it is not too much to claim that a robust civic education, which seeks to impart that “sense of continuity with generations gone before” of which Dos Passos spoke and begins the process of locating one’s life in a meaning far larger than oneself, is an important step back from the lonely precipice upon whose brink we find ourselves. We have not a moment to lose in getting started.