50 Core American Documents: Required Reading for Students, Teachers, and Citizens

Christopher Burkett

April 24, 2017

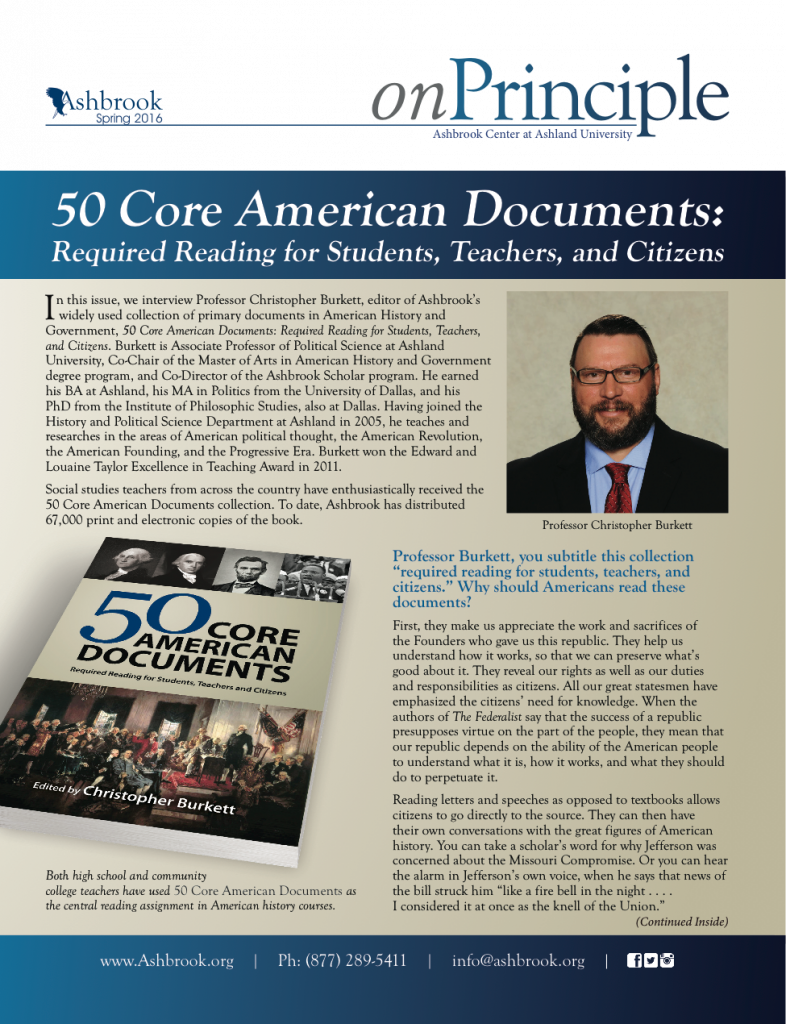

In this issue, we interview Professor Christopher Burkett, editor of Ashbrook’s widely used collection of primary documents in American History and Government, 50 Core American Documents: Required Reading for Students, Teachers, and Citizens. Burkett is Associate Professor of Political Science at Ashland University, Co-Chair of the Master of Arts in American History and Government degree program, and Co-Director of the Ashbrook Scholar program. He earned his BA at Ashland, his MA in Politics from the University of Dallas, and his PhD from the Institute of Philosophic Studies, also at Dallas. Having joined the History and Political Science Department at Ashland in 2005, he teaches and researches in the areas of American political thought, the American Revolution, the American Founding, and the Progressive Era. Burkett won the Edward and Louaine Taylor Excellence in Teaching Award in 2011.

Social studies teachers from across the country have enthusiastically received the 50 Core American Documents collection. To date, Ashbrook has distributed 67,000 print and electronic copies of the book.

Professor Burkett, you subtitle this collection “required reading for students, teachers, and citizens.” Why should Americans read these documents?

First, they make us appreciate the work and sacrifices of the Founders who gave us this republic. They help us understand how it works, so that we can preserve what’s good about it. They reveal our rights as well as our duties and responsibilities as citizens. All our great statesmen have emphasized the citizens’ need for knowledge. When the authors of The Federalist say that the success of a republic presupposes virtue on the part of the people, they mean that our republic depends on the ability of the American people to understand what it is, how it works, and what they should do to perpetuate it.

Reading letters and speeches as opposed to textbooks allows citizens to go directly to the source. They can then have their own conversations with the great figures of American history. You can take a scholar’s word for why Jefferson was concerned about the Missouri Compromise. Or you can hear the alarm in Jefferson’s own voice, when he says that news of the bill struck him “like a fire bell in the night . . . . I considered it at once as the knell of the Union.”

What do primary documents tell us that textbooks cannot?

Primary documents give us direct access to what was really going through the minds of people who played a pivotal role in history. If you just want to be given someone else’s interpretation of history, read a textbook; it’s an easy way out. Reading through the debate at the Constitutional Convention is hard. Yet it’s rewarding, because it gives us an opportunity to think through the issues they had to wrestle with and that we still have to wrestle with. The Founders said the major virtue citizens need is to be able to think for ourselves. Reading primary documents helps you develop that virtue.

A textbook tells you what somebody else thinks you need to know about an issue. So it becomes something to memorize before the test, but it doesn’t stick long-term. By contrast, when you read the argument that takes place between John C. Calhoun and Abraham Lincoln on whether a state has a right to secede, you participate in it yourself, you understand what is at stake, and you remember this.

How did you select these 50 documents from among the thousands on Ashbrook’s Teaching American History website?

Through input from faculty who regularly teach in our programs, we compiled a list of approximately 100 key documents. To winnow this down, we asked ourselves what’s important in the American story. First of all, what do we believe as Americans? This pointed us to the Declaration of Independence and a letter in which Jefferson, 50 years after the Revolution, speaks of principles that he says make up “the American mind.” Then we asked: What kind of government did Americans choose to help us live up to our principles? This pointed to the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and documents showing the debate over the Constitution’s merits. Next, Americans had to figure out how to implement this government, making necessary laws and dealing with the tension between the powers of the national government and the state governments. A major issue preoccupying American discourse between the Founding and the Civil War was the challenge of slavery to our stated beliefs in the Declaration. We chose documents that revealed the Constitutional issues with regard to slavery.

By then, we saw that we were telling our country’s unfolding story of liberty and self-government. Americans argue over what those things mean and the form they should take. As a people, we are constantly trying to live up to the high expectations of the Declaration: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” That’s America’s mission statement. In a business, the mission statement is not what you’ve already achieved but something you work toward. Americans have had a lot of work to do to live up to the standards set by the Declaration.

Some of the documents are written in an older style of English that is difficult for current readers. What advice would you offer people reading the documents for the first time?

First, get a dictionary! James Madison uses some big words rarely used today. But by and large, the meanings of the words have stayed the same.

That doesn’t solve every problem, because sometimes the syntax is difficult—the order these writers put words in. And in some of the older documents, sentences are very long. The first paragraph of the Declaration is one long sentence. It helps to break it down into six or seven clauses and figure out what each clause is saying. Beyond that, it’s like reading Shakespeare. The more you hear it, the easier it is to understand. I recommend that students read documents out loud, repeatedly. It slows down the reading, and forces you to find the tone and rhythm of the words, which often reveals the meaning.

What feedback have you gotten from teachers using the collection?

I’ve heard from many teachers who use these documents in class. Teachers are expected to cover lots of history at a brisk pace to prepare students for tests, so taking time to analyze an original document involves some risk. But when they take the risk, teachers are pleasantly surprised at their students’ ability to understand what earlier Americans wrote.

Primary documents work in what teachers today call the “flipped” classroom: an approach that shifts historical lectures into homework assignments and saves class time for close reading and discussion. Teachers assign one of the many educational films available online, or a slideshow they’ve prepared themselves, as homework. Students get an overview of the historical context the night before class, then the next day go through a document under the teacher’s guidance. Later, students analyze the documents in small groups, devoting the majority of class time to discussing the issues the documents reveal.

Teachers say that using original documents lets them teach in the most effective way: not by drilling students to memorize facts, but by helping them learn to read and analyze. Good social studies teachers don’t insist on a single “right answer.” They let those who lived in the past tell their own stories. Then they push students to think about what the voices from the past say. One teacher said, “We teachers are good at throwing an idea out on the table and seeing what students do with it.” That approach prepares students to become responsible citizens, because it teaches them to reason through problems.

Did you expect the document collection to be as popular as it is among teachers?

I wasn’t thinking that the collection would become popular; I was thinking it would be useful. Through our Master of Arts in American History and Government degree program, and through other outreach efforts, we’ve built a long working relationship with many teachers. They tell me that 50 Core American Documents differs from other document collections available. It lacks a political bias, because it includes voices from both sides of an issue, each prefaced by an introduction that simply presents its historical context. We offer two or three guiding questions that teachers can build on to generate discussion.

The most surprising thing I’ve heard is that a number of teachers have asked their students to read all 50 of the documents. Some have made it their “textbook” for a course; others assign it as independent reading, asking their students to pick favorite documents from which to write essays. Teachers say that students can take in the purpose a document served when it was written and then make it relevant to things happening today. One teacher assigned Washington’s Farewell Address, which led to a conversation about what America should be doing in foreign policy today.

Teachers do write and suggest documents to include if we expand the collection. Some have suggested documents tracing women’s suffrage and other reform movements. Another asked, “Why isn’t Eisenhower’s Farewell Address here? It captures a growing concern in the mid-twentieth century about the ‘military- industrial’ complex.” These are great suggestions; and in fact, we’re hoping to put out new volumes of documents on special themes and periods of our history. I love the feedback, because it means the documents have sparked a good discussion about the enduring issues we face in our American republic.