Teaching the Progressive Challenge to the Founding

April 22, 2022

Choosing What to Teach

American history is rich and detailed, but time in the classroom is limited. Even if one covered it all, simply “covering content doesn’t really help students learn anything,” says Cody Stafford, a history teacher at Unionville High School in Pennsylvania. Deciding what to emphasize, Stafford asks, “Which topics will most help students understand why Americans think the way we do, why our government does things the way it does, and why it’s structured as it is? For me, the Founding period and the Progressive era are the two ideological giants in the room that students really need to understand.”

Unionville, in a western suburb of Philadelphia, ranks highly on measures of school effectiveness. Stafford’s courses are challenging. In his Advanced Placement U.S. history class, he uses primary documents daily and spends several weeks teaching the writing skills students need to perform well on the AP exam. He gives particular attention to the Founders’ effort to shape a limited republican government and the Progressive effort to expand government’s role.

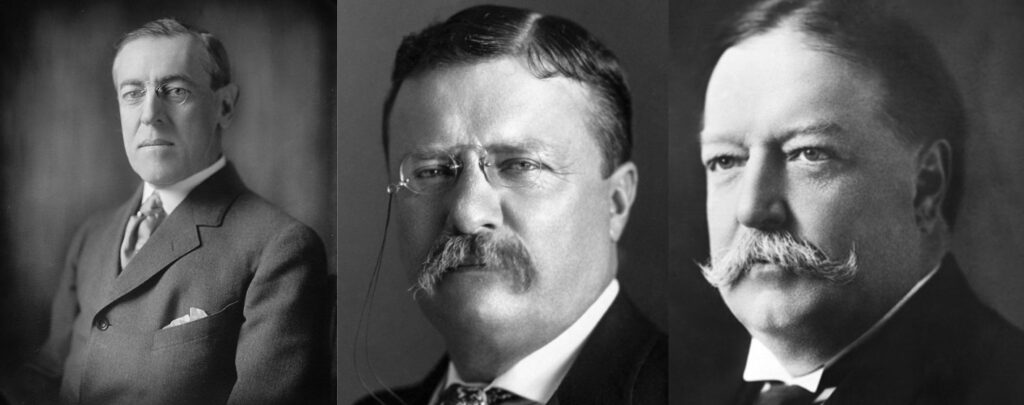

“We spend a lot of time looking at the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and key Federalist papers, as well as a couple of Anti-Federalist papers, which we read all the way through.” This helps students grasp the understanding of government that informs American history through the Civil War. Later, Stafford’s students read progressive political theory—such as the essays of Woodrow Wilson—which helps them understand the entire 20th century. “If you understand the Progressive Era, you understand FDR and the New Deal, and you understand LBJ and the Great Society. You understand how these American leaders saw the role of government.”

How the Progressives Understood Government

As an undergraduate, Stafford concentrated in European history. “I had never taken a course in American history that went past the Civil War. I knew nothing about the Progressive Era—until I came to Ashbrook,” to study in the Master of American History and Government graduate degree program. “Taking the Progressive Era course really changed the way that I think about U.S. history.”

Stafford had taught the Progressive Era as a reform movement arising in response to the unregulated business growth that followed the Civil War. It fit into a pattern of alternating laissez-faire and reformist tendencies in American politics. In Ashbrook’s graduate program, however, he came to see that the progressives introduced a completely new understanding of the role of government.

“The Founders saw government itself as the only threat to citizens’ natural rights. The progressives saw a new threat in business corporations.” Their economic might, and their status as individual persons under the law, gave them power over workers’ lives. “The only institution that could control big business was government. So they wanted to give government power to regulate those businesses.”

The progressives also felt “an overwhelming zeal for democracy” that reshaped American politics in the 20th century. Changes in electoral practices that made government more immediately responsive to the popular will would, they felt, restrain government from using its new powers unfairly. “But to the Founders, ‘democracy’ was not necessarily a good thing. They created a republic, believing that the people making decisions needed to be in a position to make those decisions”—equipped with education, political experience, and a reputation for wise decision-making.

Progressive reforms, such as the introduction of referenda and the 17th Amendment’s revision of the system for electing senators, eventuated in our current system of primary elections. This has encouraged the election of political newcomers, mavericks, and those outside the party structure.

“After the McGovern-Fraser Commission, if you’re a moderate, you’re out of luck—you’re not going to be running on your party’s ticket. The polarization we see today is a direct result of the primary system,” Stafford says. It can be difficult for students to believe that an unelected commission that met over 50 years ago could have such a huge influence on our politics today.

Ultimately, current and future generations will have to grapple with many of these issues for themselves. “I don’t know the answer to that,” says Stafford. “Do you tell people they don’t get to vote in primaries? Do you go back to the system where party bosses pick the candidates? Once you give democracy to people, you can’t take it back.” Amid these evolving political questions, it is critical that students have a firm grounding in American principles—the principles that Cody Stafford helps his students learn from the Founding documents of our history.