Lincoln: A Movie to See

December 24, 2020

My mother–now moving towards 88–hasn’t been to a movie in over ten years, yet she insisted on seeing Lincoln. I was delighted to go to a movie with Mom, happy to see every seat taken, and even more delighted to hear the applause at the end of it. I’d never been to a movie which brought forth spontaneous and heart-felt applause. And it was deserved. This is a first-class movie and its two-and-a-half hours went by unnoticed.

My mother–now moving towards 88–hasn’t been to a movie in over ten years, yet she insisted on seeing Lincoln. I was delighted to go to a movie with Mom, happy to see every seat taken, and even more delighted to hear the applause at the end of it. I’d never been to a movie which brought forth spontaneous and heart-felt applause. And it was deserved. This is a first-class movie and its two-and-a-half hours went by unnoticed.

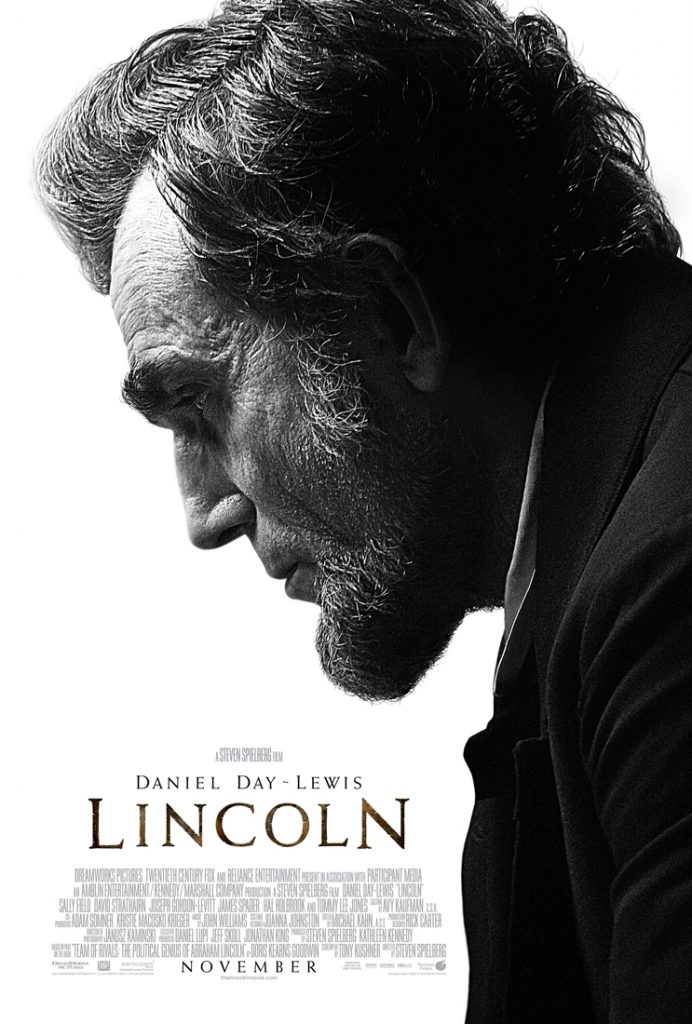

Daniel Day-Lewis portrayed perfectly the simple external figure Lincoln projected to those first meeting him. Lincoln was not an attractive man; he was awkward and gawky, with his flat-footed walk and his shoulders often wrapped in a shawl, mumbling lines from Shakespeare and Euclid and the Bible with lively eyes and a scratchy tenor voice, or telling off-color stories that, while funny and useful for the occasion, are always slightly embarrassing.

But Day-Lewis also reveals Lincoln to be internally complex. He shows Lincoln to be, as his law partner once described him, “philosophical-logical-mathematical,” always struggling to see a thing or an idea exactly and “to express that idea in such language as to convey that idea precisely.” This is why he is able to persuade, relying on the Saxon element of the English language, with its archaic simplicity. Look again at the most patriotic American speech, the Gettysburg Address, and see how few are the Latin or French based words found there. The words are old and simple and short. So their effect is energetic, bright, and sharp. It is the American poem that reminds us of our ancient faith.

This imperfect and deeply meditative Lincoln–surrounded by family chaos and war horror–agonizes over why young boys should be executed because they left their military post to see their mother. His heart knows that he would have done the same. What surprises him is that most men stayed, and thousands died. This is the man who said that if slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. He is the one who pointed out that while many people support slavery as a good, it is a good that none wants for himself. In the movie we see him rising to the heights of American statesmanship where finally law and justice become the same thing.

Because the Emancipation Proclamation was a military order, a war measure, (and applied only to those slave states actually in rebellion against the Union) and because the constitutional status of slavery might remain in doubt once the emergency was ended, an amendment to the Constitution was needed to wrap the whole thing up. So the plot of the movie–sandwiched in between the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural–is focused on the debates in the House of Representatives on the 13th Amendment and the rough-and-tumble politics it took to get it passed.

The movie wonderfully shows what politics is at its best–constitutional statesmanship navigating between liberty as its good end and the low politics that are a necessary means toward it. Even when the give and take seems rough and base, the low is always in the service of the high. In the basement of the White House–over the image of a compass always pointing north–Lincoln lectures the abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens on why the means of getting to that just end must always be varied. The radical Stevens wants to simplify it. He thinks only the principle matters; Lincoln knows better, he has a better understanding of politics. He understands that choosing what is truly the right thing is good only insofar as it can be realized. Principle needs intelligence, it needs prudence, practical wisdom, and this is politics at its best.

And this is why both principle and prudence are worth studying and doing in our constitutional republic. This is what the movie teaches and that is why it is a fine movie that should be seen (more than once) by all of us Americans, including the sons of good mothers.

Peter W. Schramm is the Executive Director of the Ashbrook Center and a Professor of Political Science at Ashland University.