Hayward in the Claremont Review of Books

December 24, 2020

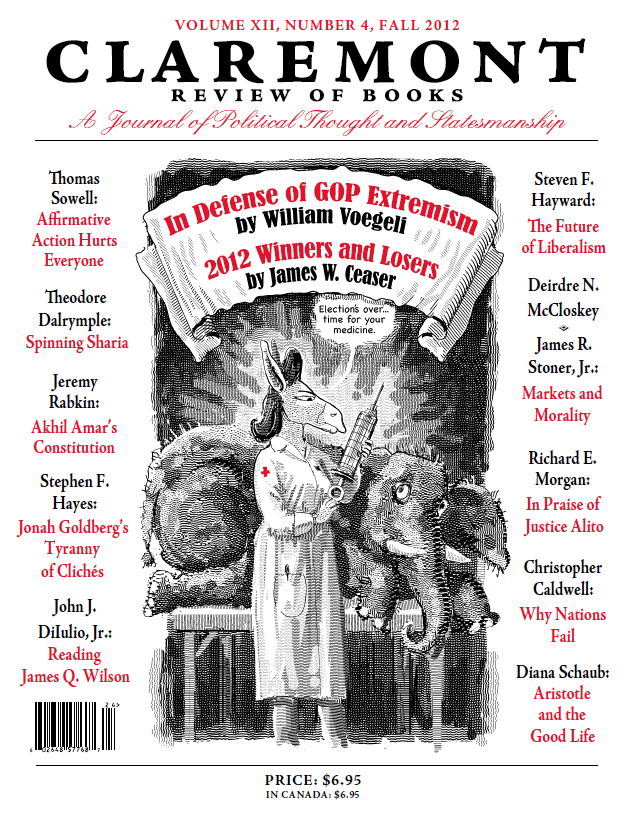

Steve Hayward, the Ashbrook Center’s Thomas W. Smith Distinguished Fellow, has an article in the Fall 2012 volume of the Claremont Review of Books. The article, “Up From Liberalism” is a review of Charles Kessler’s book I Am the Change: Barack Obama and the Crisis of Liberalism.

Up From Liberalism by Steven F. Hayward

The only thing worse for liberalism than President Barack Obama’s defeat might turn out to be his reelection. After Mitt Romney’s dispiriting loss in November, conservatives may at last move beyond the comfortable thesis that the United States is an essentially “center-right” nation. They do not need to rend their garments that the country is irretrievably lost, but nor should they settle for debates about tactical adjustments over immigration and other social issues. Conservatives must finally understand and duly repudiate the modern American liberalism Obama champions. His narrow victory does not represent a decisive point-of-no-return so much as one more step in a long train of significant turning points.

Clarity about Obama’s liberalism is especially important because of his enormous success, abetted by a sympathetic and uncurious media, in obfuscating it. Liberals and the media (but then, I repeat myself) say he is just another “pragmatist” like Franklin Roosevelt— or as Cornel West derisively put it after the election, “a Rockefeller Republican in blackface.” Some on the Right, on the other hand, think they behold a real-life Manchurian candidate. Obama’s trendy educational background, dubious company (Bill Ayers, Derrick Bell, Reverend Jeremiah Wright), and past work as an Alinskyist agitator seem to bespeak radical designs to bring the nation down. But these furies and confusions on both the Left and the Right have missed the ways in which the president is a kind of culmination of the modern liberal project, and what his “audacity of hope” means in practical terms for the future.

This bigger story behind and beyond Obama is the subject of Charles R. Kesler’s superb new book, I Am the Change: Barack Obama and the Crisis of Liberalism, which aims right for the heart of the Left’s revolution in American politics. Readers of the Claremont Review of Books will not be surprised to learn that Kesler, the journal’s editor and a distinguished professor of government at Claremont McKenna College, carries off his argument with insight, learning, and wit.

Far from being something alien to American politics, Obama fits comfortably into the tradition of the 20thcentury Progressive Movement—and is a real-time working out of the contradictions and weaknesses building in liberalism since Woodrow Wilson first won the Oval Office exactly 100 years ago. Though the title I Am the Change might suggest a narrow excursion into Obama’s personal narcissism, the president’s overweening self-regard is not merely a personal conceit, Kesler argues, but a political conceit with deep philosophical roots that suffuse the modern liberal mind. To understand Obama, then, is really to answer the question “what does it mean anymore to be a liberal?”

Obama may have thought more about the meaning of contemporary liberalism than most denizens of the American Left, but it’s a low bar to reach. He shares modern liberalism’s essential laziness arising from its philosophical presumption, which helps explain not only his own hauteur but also his surprise at Romney’s robust performance in the first debate. (That same lazy presumptuousness explains some of the bizarre liberal reaction to this book, as we shall see.)

In order to understand Obama and what he reveals about today’s liberalism, it is necessary to put him in the context of what Kesler calls the “three powerful waves” of liberal reform—inaugurated by Wilson, FDR, and Lyndon Johnson—to which Obama hopes to add the fourth. This masterly tour through 20th-century liberal thought is essential to piercing Obama’s rhetorical conceit that he is a “postpartisan” political figure out to transcend the bitter political divide of the Baby Boom generation. Unlike Bill Clinton, whose politics Obama didn’t think bold enough, “Obama assumes the Reagan Revolution is not here to stay,” Kesler writes, “because the Obama Revolution is just beginning…. [It aims] to prove that the era of big government is not over.” Obama believes that liberals can win the debate over the size and scope of government, in part because he believes liberalism’s lasting victories of the past century, despite the Reagan-Gingrich-Bush interlude, provide the high ground from which to march further. And liberals, Kesler wryly reminds us, “are very fond of marching.”

The arc of liberalism Kesler traces is not merely the tale of more and bigger and costlier central government, it is the story of a shift in our governing principles regarding individual rights, the meaning of constitutionalism, and, above all, the new idea of unending Progress with a capital P, which made bigger government not simply possible but supposedly necessary.

The changes liberalism wrought over a century, though radical in substance, proceeded by slow, subtle steps, gradually amounting, as Kesler has written in the CRB, “to a prescription for an American character increasingly unfit for self-government.”

In many ways Obama is the uncanny epigone of Woodrow Wilson, whose political philosophy was a strange amalgam of Hegel, Burke, Darwinism, and that homegrown American ideology, Pragmatism, all of which congealed into a doctrine that made historicist assumptions the philosophical core of modern liberalism. Kesler disentangles Wilson’s often convoluted prose and confusing concepts to see through to the essentially radical ideas cloaked in a moderate, even slightly conservative, disposition.

Wilson saw Darwinian evolution as an alternative to socialist revolution. His embrace of the “living constitution” went beyond jurisprudence to include all three branches of government, and his self-conscious inflation of the idea of presidential “leadership” has transformed the way every candidate and president has conceived the executive office ever since—and not for the better. It was Wilson who bestowed “the vision thing,” as George H.W. Bush once ironically but correctly disparaged it, as a prerequisite for all subsequent presidents. The American Founders would have been wary of Wilson’s conception of the popular presidency, if not outright appalled by its demagogy. From elevating the president into the one man with both the “vision” of the future and the will to lead the American people to a collective destination of which they themselves are unaware (“men are as clay in the hands of a consummate leader” was Wilson’s famous formula), it is a straight line to Michelle Obama’s 2008 comment that “Barack will never allow you to go back to your lives as usual, uninvolved, uninformed.”

Wilson’s seemingly moderate bearing disguises the other profound consequences of his radical break with the founding’s natural rights philosophy. He eroded if not completely eliminated the older liberal suspicion of state power: 18th-century liberalism overthrew the divine right of kings; 20th-century liberalism celebrated the divine right of the State. He championed administrative expertise, which led to the continual expansion of unlimited, unelected bureaucracy. Above all, Wilson’s deprecation of the founders’ understanding of just government arising from individual natural rights set the stage for drastically altering the relationship ever since between American citizens and their government.

This last point remains difficult to grasp largely because of the second wave of liberal reform that Franklin Roosevelt accomplished through the New Deal. Kesler rejects the standard view of FDR as a pragmatic politician with no firm governing philosophy, a superficial reading of the New Deal’s erratic lunges and Roosevelt’s own rhetorical embrace of experimentation.

“To many historians and biographers,” Kesler notes, “Roosevelt was hardly worth taking seriously as a thinker.” Nevertheless, he “was the second great captain of liberalism,” with “successes so lasting that liberal public policies and, even more important, the assumptions behind those policies, became ruling elements in our public life…. Roosevelt’s own political genius may have owed more to insight than reflection, but it has been underrated regardless.”

FDR recognized that Wilson’s more or less open filial impiety toward the American Founding was politically ill-advised. Roosevelt anchored the new progressive liberalism in an affirmation of the founding that upon closer inspection revealed deep affinities with Wilson’s critique of it. (See, for example, FDR’s 1932 Commonwealth Club address). In 1938 Roosevelt said in a radio address: “Think of the great liberal achievements of Woodrow Wilson’s New Freedom, and how quickly they were liquidated under President Harding. We have to have reasonable continuity in liberal government in order to get permanent results.” In order to achieve that permanence, FDR claimed for liberalism sole possession of the founding’s “title deeds.” He did this by slyly severing the Constitution from its grounding in the natural rights doctrine of the Declaration of Independence. By separating rights from nature, he turned our understanding of rights upside down, paving the way for so-called economic rights and the government programs to secure them. He spoke openly of “redefining rights” and establishing a new social contract. Under this contract, Kesler summarizes, “when the central government is on the side of the people, then according it more power will not diminish but enhance the people’s rights. One could call this the First Law of Big Government: the more power we give the government, the more rights it will give us.”

Although the New Deal was a staggering political success, Kesler argues that it set up serious long-term problems for liberalism. The programmatic nature of economic rights fractured Americans into more and more grasping special interest groups, diluting the New Deal’s high idealism. Kesler concludes his treatment of FDR with a premonition of trouble ahead:

But rather than permanently lifting the moral tone of American life, the welfare and regulatory state plunged our politics into an amoral scramble for power, benefits, and influence that looked all the more tawdry next to the high hopes Roosevelt had raised. This interestgroup or social-welfare Darwinism proved a lasting part of liberalism, and helped spur the greater disillusionment to come in the 1960s.

That disillusionment arrived on the heels of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, when liberalism was undone by a pincer movement of its own making. The Great Society represented a substantive leap beyond the New Deal for liberal social policy—a graduation from civil engineering (think Works Progress Administration) to social engineering (Community Action Program, Head Start, etc). Kesler’s formula is that the quantitative liberalism of social insurance and pro-labor measures gave way to a qualitative liberalism that promised not just a chicken in every pot but “self-actualization” (a favorite buzzword of the time) itself. With his expansive rhetoric, Johnson abetted a strain of thought present in liberalism since Wilson but not very far advanced before the 1960s—personal fulfillment, which manifested itself in what came to be known as “lifestyle liberalism” or the exaltation of “the self-creating Self.” As Kesler explains,

the Great Society accepted and encouraged— how consciously is a different question—the New Left’s inclination to base politics increasingly on issues of personal identity, gender, and sexuality, and ‘postmaterialist’ concerns like environmental activism…. Mainstream liberalism found it hard to confront the radicals because so many of their premises were its, too.

Between the rise of a more radical New Left born of qualitative liberalism’s own insatiability and the Baby Boom’s demographic bulge, which magnified the social unrest, LBJ was soon engulfed by a civil war between the political Left and the cultural Left. It ended with Johnson’s abdication, and “the long whimper of white liberal guilt.” “The deepest truth,” Kesler observes,

is that the Great Society destroyed the Great Society. Its soaring expectations, its utopian promises, could not be fulfilled in ten years or a hundred years. What it proffered was the satisfaction, in principle, of all material and spiritual needs and desires.

Liberalism shuffled along through the 1970s as a spent force, with Jimmy Carter unable to end the malaise or revive the creed. The salient aspect of liberalism in its terminal phase is that its increasingly programmatic and bureaucratic character—“big government” in the vernacular—transformed government itself into “a cynicism-generating machine.” As Kesler puts it, “The Sixties’ more enduring legacy was the strange combination, still very much with us, of a more ambitious State and a less trusted government than ever before.” The way in which Ronald Reagan swept in to pick up the ruins of exhausted liberalism had to come as a surprise to those whose historicism and celebration of willful passion (i.e., “commitment”) had caused liberalism to abandon sustained self-reflection.

Which brings us to Barack Obama, whom supporters and media cheerleaders insist on portraying as another non-ideological pragmatist with only modest ambitions (though none of them can explain why he didn’t emulate Bill Clinton’s successful “triangulation” strategy in the face of a resurgent GOP after the 2010 election). This theme does an injustice to Obama’s own large ambitions and his place in modern liberal thought, both of which are not hard to tease out of his writings and speeches. Although he is no deep thinker, he doesn’t need to be, given how fully liberal assumptions of unidirectional progress and unending reform have become the basic furnishings of modern politics. Still, he is clever, purposeful, and more rhetorically deliberate than Clinton ever was.

The three former waves of liberal reform provided ample political capital when electoral fortunes finally smiled again upon the Democratic Party in 2008. The object of the fourth great wave of liberal reform—for that is clearly what Obama aspires to—is to revive unapologetic liberalism as a governing creed. Rather than patching it up and trimming to fight another day as Clinton had, Obama doubled down on liberalism. He has not been content with poll-tested, short-term personal success. Instead of addressing the stagnant economy, his desire to play the long game drove him to pass at all cost the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (to which Kesler gives ample and expert attention). “We did not come here just to clean up crises,” Obama told Congress; “We came to build a future.”

Despite his re-election, Obama’s vision of the future still faces three problems: 1) the combined weight of Obamacare’s unpopularity, our protracted economic doldrums, and a continuing conservative opposition; 2) the internal tensions and attenuation building in modern liberal thought over the past century; and 3) an unsustainable and soon-to-be bankrupt welfare state that must contract. To the book’s central question—“is liberalism on its last legs, or about to be reborn?”— Kesler’s own answer is the former. It remains to be seen not just whether Obamacare—the administration’s central achievement—will thrive and become accepted by the American people, but whether liberalism itself can survive the looming fiscal catastrophe that is unraveling what Walter Russell Mead has called “the blue state model” of governance. James Piereson recently argued in the New Criterion that Obama is destined to take his place alongside John Adams, James Buchanan, and Herbert Hoover as the last president of a dying political order and mode of governance.

Though Kesler doesn’t put it this way, his argument suggests conservatives should cheer up: the future is slipping away from liberalism. Despite the successes over the past century, liberalism’s philosophical hollowness and actuarial imbalances are catching up to it. “Liberalism can’t go on as it is, not for very long,” Kesler writes; “[i]t faces difficulties both philosophical and fiscal that will compel it either to go out of business or to become something quite different from what it has been.” He points to the irony of liberals deciding to call themselves “progressives” again: “liberalism is in a bad way when it has lost confidence in its own truth, and it’s an odd sort of ‘progress’ to go back to a name it surrendered eighty years ago.” Obama is the apotheosis of all of progressive liberalism’s worst traits, including the penchant for willed “visions” from the top, an impatience with ordinary politics and constitutional forms, a disdain for the American Founding (Kesler’s exegesis of how and why Obama fundamentally agrees with Reverend Jeremiah Wright’s “God damn America!” is not to be missed), and the unquestioned assumption that “progress” culminates in him personally. (This, by the way, is why Obama will eventually become a much more obnoxious and irritating ex-president than Carter.)

Though this might seem willfully optimistic after the long catalogue of liberal success that comprises much of the book, Kesler reminds us that if Communism could “collapse of its own deadweight and implausibility, why not American liberalism?” He acknowledges that more than gravity will be required to bring it down. American statesmen and the American people need to do their part, too. Liberalism’s wager—and Obama’s ambition in particular—is that no Republican who wins the White House again can overthrow or even pare back the massive and still evolving state apparatus put in place by a century of liberalism. This is why the question of Obamacare’s repeal or unwinding is so crucial. Never mind taking Big Bird off the dole, rolling back Obamacare, argues Kesler, would shatter the superstition that liberal “progress” moves inevitably in one direction. Moreso than an Obama defeat, it would have shaken liberalism’s confidence. Although a second term makes that outcome much more remote, the flaws that will emerge as Obamacare is implemented mean that its sustainability is not assured.

The fate of Obamacare aside, that such a shakeup is necessary is evident from the liberal reaction to Kesler’s book, especially by Mark Lilla in the New York Times Book Review. Lilla, an able and provocative intellectual historian and critic, dismisses I Am the Change because its author takes Obama’s stated ambition seriously. It is an odd criticism to say that your argument should be rejected because you think too well of your opponent. To hear Lilla tell it, Obama is “a moderate and cautious straight-shooter,” and there isn’t much of a progressive tradition to draw upon in thinking about the president—or anything else. More embarrassing is the tacit premise that Obama doesn’t deserve comparison to, or placement within, the grand tradition that preceded him, chiefly because his modest achievements (including the holy grail of universal health care) don’t rise to the canonic level of the liberal giants of old. Whether Obama agrees with or wishes to build upon the Progressive tradition is regarded as unworthy of consideration, as though Progressivism itself is something best regarded as a Smithsonian Institution curiosity. It is an odd thing for someone to profess to take political ideas seriously but not to take statesmanship seriously.

Liberals are understandably riding high after Obama’s dramatic re-election. But after the party will come the hangover. Twenty-five years ago Harvey Mansfield wrote about “a liberalism that is politically exhausted and bored with itself.” The way in which so many liberals like Lilla have dismissed as meaningless rhetorical flourishes Obama’s self-proclaimed “audacity” and ambition to “transform the country” reveals a liberalism that increasingly disdains the purposeful ambition and public argument it once championed, even as it cheers on every possible incremental enlargement of the modern State. The ultimate irony of Barack Obama—as the indispensable I Am the Change makes plain—is that he has been regarded more seriously by a conservative than by almost any liberal intellectual. That can’t be a good sign for liberalism’s future.